Junction City Stories II

Lions Club: Predators and Prey, The Karens of Oak Meadows, and other stories

The Rise of Jefferson

Part I: Early Whispers

In a town where nothing of note was supposed to happen, the arrival of Tweed Jefferson was the first genuinely interesting event since the time a tractor-trailer overturned on Highway 99 and spilled several tons of onions into the intersection. The onions had rotted in the August sun, perfuming the town for weeks with a pungency that drove children to hold their noses as they walked to Dari Mart. Even years later, residents spoke of “The Great Onion Spill” with the kind of reverence usually reserved for baptisms, weddings, and the Duck football schedule.

And yet, the Onion Spill had nothing on Jefferson.

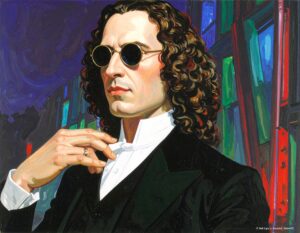

He did not arrive with fanfare, but with a sort of quiet, insinuating presence, the way mold introduces itself into an otherwise respectable loaf of bread. Nobody could point to the exact moment he first appeared. Some said they saw him at the library, hunched over back issues of The Tri-County Tribune, turning the pages with surgical care. Others insisted he was glimpsed at Thistledown, plucking tomatoes with a disdainful precision that suggested he was weighing not just their ripeness but their moral worth. One woman swore she saw him at Safeway, buying a black coffee at six in the morning, staring so intently at the donut rack that she abandoned her purchase of maple bars and left without a word.

He had the sort of face that people remembered without knowing why – angular, unhurried, as though carved not by a loving God but by a municipal committee. His suits were tailored but unfashionable, the sort of garments that suggested both seriousness and disregard for the fickle churnings of taste. He walked as though Junction City were already a stage built for his performance, as though every crack in the sidewalk and every squeak of the Dairy Queen sign had been rehearsed for his entrance.

The children, whose instincts are sharper than they are given credit for, dubbed him “Count Dracula’s cousin” after a single sighting at the park. Adults were less direct but no less wary. A silence seemed to travel with him. An atmospheric hush that made one notice the hum of fluorescent lights or the faint dripping of an irrigation hose.

What he wanted – or whether he wanted anything at all – was, at first, a matter of speculation. This speculation was carried on primarily in line at the post office and, more elaborately, in the beauty parlor, where narratives are known to germinate with alarming fertility. Some suggested he was a developer from California, sniffing around for land to strip bare in the name of progress. Others thought he might be a disgraced professor from the university, banished for reasons too lurid to be spoken aloud, but easily insinuated with a raised eyebrow. A smaller faction held that he was an emissary of some higher government authority – sent, perhaps, to conduct an experiment in rural governance using Junction City as his terrarium.

Jefferson himself did nothing to confirm or dispel these rumors. He moved with deliberate inconspicuousness, showing up at the same coffee shop each morning to order tea (“never coffee,” one barista confided darkly, as if this proved everything), reading fat, inscrutable books that looked like they had been pulled from the locked cabinet in the library nobody dared open. He wrote in notebooks – always with a black gel pen, which in Junction City was considered a little extravagant, like wearing cufflinks to Les Schwab.

It was at a council meeting that he first made his true presence felt.

The meetings were, by tradition, sparsely attended affairs, attracting only the morbidly civic-minded and those with grudges involving zoning regulations. On that particular Tuesday, the chamber was nearly empty except for a man upset about his neighbor’s fence, a woman complaining of potholes near the elementary school, and the usual retinue of councilors who sat at the dais like reluctant actors in a long-running play no one wanted to see.

And then Jefferson rose. No one had seen him enter, yet there he was, tall, severe, the color of his suit suggesting both midnight and mildew, depending on how the flickering lights struck it. He did not speak immediately, which in itself was remarkable; in Junction City, silence in public was usually reserved for funerals and moments when everyone was trying to remember the name of someone else’s cousin.

When at last he spoke, his voice was calm but carried the faintest undertone of condescension, like a teacher explaining arithmetic to children who had already failed it once before.

“I have observed,” he straightened his vest. “That Junction City has sidewalks unfit for walking, parks unfit for lingering, and a Main Street unfit for anything resembling civic life. You call yourselves a community, but what I see is a scattered collection of houses clinging to a highway, united only by proximity to a gas station.”

A hush fell, broken only by the cough of the man angry about his neighbor’s fence.

“You require,” Jefferson continued, “a certain…reconfiguration. A walkable city, where people meet by chance rather than by appointment. Green spaces that do not reek of mildew and neglect. A market that is more than a sad congregation of wilted kale. You require what you do not yet know you want.”

The councilors shifted uneasily, each glancing at the others as though one of them might leap up and object. None did. Jefferson did not so much sit down as fold himself back into place, leaving behind the faint odor of inevitability.

From that moment, he was no longer a curiosity but a force.

The first signs of his influence were subtle. A new crosswalk here, a bench there. Then came the pedestrian plaza downtown, where people found themselves lingering as though compelled. The Dari Mart installed a bike rack; nobody knew why, but within a week it was full. The parks were suddenly immaculate, their grass suspiciously uniform, the broken swing replaced before anyone had a chance to complain. Even the police began to appear more often – not in cars, but on foot, as though they had been told to infiltrate the very rhythm of the streets.

None of this could be traced directly to Jefferson. He held no office, signed no documents, and spoke rarely. Yet when he did appear – at a ribbon cutting for a community garden, or leaning quietly against a lamppost as the farmers’ market bustled – people felt the changes were somehow his. They began to speak of him in half-joking tones, calling him “Our Shadow Mayor,” or more darkly, “The one who really runs things.”

And yet, when pressed, no one could say precisely what he had done. His suggestions at council meetings were framed as observations, his critiques delivered as if from a higher authority that merely reported facts rather than opinions. It was, after all, simply true that the sidewalks were cracked, the parks shabby, the storefronts empty. Only Jefferson seemed to notice that such truths, when spoken aloud, took on the quality of commandments.

By autumn, the town was transformed in ways that were undeniable and yet difficult to trace. The air seemed fresher, though the factories still churned. People walked more, though the distances remained the same. Children played in parks without fear of broken glass and the old gathered on benches as though newly invented.

It was progress, certainly. But progress with an aftertaste.

At the Beer Garden, one could overhear mutterings: Had you seen the way he stared at the mural on Main Street, as though judging it unworthy? Did you notice how he speaks of “reconfiguration” as though we were all pieces on a chessboard? And why does he never laugh?

The town, in its collective heart, could not decide whether Jefferson was a blessing or dubious omen. What was clear was that he was inevitable. Like the Onion Spill before him, he had come to Junction City unbidden, and he was not leaving soon.

Part II: The Reforms

By winter, the name “Jefferson” had become a kind of shorthand for inevitability.

At the Dari Mart, when the clerk restocked the milk cooler before dawn and found a gleaming new refrigeration unit installed overnight, he muttered, “Jefferson.” When an oddly tasteful lamppost appeared at the corner of Sixth and Holly, its base stamped with no city contractor’s name, people simply pointed and said, “That’s him.” It was not admiration so much as resignation, the way one might shrug at a rising river and say, “Flood’s coming.”

The City Council, traditionally sluggish, now moved with baffling velocity. Budget approvals passed without dissent, committees agreed without debate, and permits were signed as though by invisible hands. When asked how these changes had been expedited, Councilwoman Jenkins could only blink and say, “I don’t recall. But I suppose it was the right thing.” Then she would smile too widely, as though compensating for some foggy gap in memory.

The townspeople themselves were altered, subtly. Old men who had once gathered in the café to argue about tractor parts or taxes now spoke earnestly about “walkability indices.” Teenagers, once devoted to slouching behind the bleachers to vape, now congregated around the new public art installation: a peculiar obelisk that emitted faint music when the wind struck its hollow channels. Nobody claimed credit for the obelisk, but everyone felt it bore Jefferson’s hand – its angles severe, its surfaces polished to a sheen that reflected more shadow than light.

At first, the reforms seemed charming, even enviable. Other towns along Highway 99 began to grumble that Junction City had somehow leapt ahead, its potholes filled, its sidewalks crisp, its parks lush as golf courses. A journalist from Eugene even drove out to write a flattering piece titled “The Little City That Could.” She interviewed several locals, all of whom, when asked how the improvements had been accomplished, frowned as though the questions were ill-formed.

“Well,” one farmer said slowly, “I suppose we’ve always had it in us. We just needed the right push.”

The journalist asked who provided the push. The farmer shrugged. “It’s just happening.”

She noted, in her article, that Junction City had developed “a mysterious civic cohesion.” Readers elsewhere found this charming. The residents of Junction City found it accurate but disturbing, like a photograph that captures a family resemblance no one wishes to acknowledge.

The most visible of Jefferson’s fingerprints lay upon the farmers’ market.

What had once been a ragtag collection of tables sagging beneath floppy zucchini and jars of questionably-preserved jam now became a marvel of organization. Stalls were aligned with military precision, vendors’ offerings curated so that no two booths duplicated each other’s wares. The bread seller, who once showed up late and disorganized, now arrived at dawn, his loaves stacked in perfect pyramids. The honey vendor’s jars gleamed under some unseen lighting scheme, their labels standardized as if by decree.

Nobody recalled deciding on these changes. They simply…happened. One morning the market was a jumble, the next it was an exhibit fit for a metropolitan magazine spread.

The crowds responded accordingly. Shoppers moved not in the usual bumping, halting flow but in a strangely fluid procession, as though nudged invisibly toward certain stalls. A woman found herself buying a jar of olives she did not remember tasting. A man carried home a bag of mushrooms he swore he’d never have touched. The cash exchanged was real enough, the produce authentic, but the transactions carried the faint aftertaste of compulsion.

And there, at the periphery, stood Jefferson. Not selling, not buying – merely observing. His hands folded behind his back, his gaze scanning the market with the satisfaction of an artist watching his canvas dry.

Children, emboldened by curiosity, sometimes asked him questions.

“Mister, why’s the bread stacked like that?” one boy asked, pointing to the pyramids.

“Because it is correct,” Jefferson replied softly, without looking down.

The boy did not ask again.

At City Hall, things grew stranger still.

Council meetings, once soporific affairs, now attracted crowds. Not large crowds – Junction City was never a place for mass gatherings – but enough to fill the small chamber with a nervous energy. Jefferson never sat among the councilors, nor behind the lectern. Instead, he hovered at the back, arms crossed, his expression unreadable.

Yet when debates grew tangled, councilors would glance in his direction. A subtle tilt of his head, a narrowing of his eyes, and suddenly motions were passed, disputes settled, compromises reached. He never spoke. He never needed to.

Councilwoman Jenkins, once a formidable personality known for her tirades about road maintenance, now spoke of “strategic alignment” and “urban symphonies.” When asked by a local reporter whether these phrases were her own, she looked startled, as though caught plagiarizing. “Of course,” she said stiffly, though her eyes flicked toward Jefferson at the back of the room.

The budgets reflected his touch, too. Money appeared for projects no one remembered proposing: a “Civic Harmony Pavilion,” a “Pedestrian Encouragement Program,” a “Market Synchronization Fund.” Line items bloomed like mushrooms after rain, inscrutable but irresistible.

When the mayor was asked how these programs had been approved, he chuckled nervously. “Well, it’s all in the minutes, I suppose. Nothing unusual.”

Yet when the reporter checked the minutes, they were curiously vague. “A discussion was held,” one entry read, “and consensus was achieved.” No details, no votes recorded, only consensus – as though the decisions had simply emerged, like mist condensing on glass.

Most unsettling of all was the change in the people themselves.

At first, citizens merely expressed surprise at the town’s improvements. “Nice to see the potholes fixed,” they’d say. “Strange, but nice.” Then came admiration. “We’ve really pulled together lately, haven’t we?” Soon after, pride. “Junction City, now that’s a place to live!”

And beneath pride, something quieter. Obedience.

Nobody jaywalked anymore. Nobody littered. Teenagers stopped scratching their initials into picnic tables. The graffiti behind the feed store – Go Ducks in sloppy green paint – vanished overnight, and no one dared replace it. People queued politely at the food trucks, even when the lines stretched absurdly.

There was no law against misbehavior. Yet the very idea of rebellion seemed to have evaporated.

One evening, a young man attempted to skateboard down Sixth Street, as was his custom. Halfway down the block, he slowed, dismounted, and carried the board under his arm. “Just didn’t feel right,” he explained later, unable to articulate why.

Parents noticed their children spoke less of what they wanted and more of what they ought. A girl who had once begged for ice cream now said, “We should probably have vegetables first.” A boy who had resisted bedtime declared on his own, “It’s optimal for tomorrow if I rest now.”

The parents, pleased but uneasy, whispered among themselves: This isn’t normal. This is better, but it isn’t normal.

Through it all, Jefferson remained silent, watchful, unaccountable.

He never raised his voice, never issued a demand. Yet people felt him everywhere. His shadow seemed longer than it should be, his eyes always present even when he was absent.

At night, residents dreamed of corridors lined with trees, of plazas filled with silent crowds, of obelisks humming faintly under starlight. They awoke refreshed, yet with a lingering chill.

At the café, old men would start to complain about “That Jefferson fellow” but stop halfway through, unable to form the words. At the beauty parlor, women gossiped about him but in tones more reverent than scandalous, as if speaking of a priest rather than a neighbor.

One child, asked in school to draw “Our Town,” sketched not houses or streets but a tall figure standing in the center of a plaza, his arms spread wide. When the teacher asked who it was, the child said simply, “The man who tells us how to walk.”

The teacher laughed nervously and filed the drawing away in her desk, where she would look at it every so often with a growing sense of unease.

By spring, Junction City was cleaner, richer, and stranger than anyone could remember. The obelisk sang more often. The sidewalks gleamed unnaturally. People moved with a harmony they did not question.

And always, Jefferson watched – silent, patient, as if the true transformation had only just begun.

Part III: The Gathering Dread

By early summer, Junction City no longer resembled itself. The banners over Main Street no longer sagged; they billowed with crisp authority, declaring themes like Harmony Week and Civic Unity Days in lettering too elegant to have been printed by local hands. The lawns, once patchy with moss or dotted with dandelions, now grew with uniform lushness, as if maintained by some unseen gardener. Even the dogs, traditionally prone to wild barking and escape, now walked calmly beside their owners, leashes slack, eyes oddly focused.

Yet beneath the polish, unease festered.

People began to notice things. That conversations often faltered when Jefferson drew near, as though words were siphoned from their throats. That nobody remembered voting for half the projects under construction. That the children’s songs, sung at recess, now carried strange refrains – hymns of order and symmetry.

The Bi-Mart clerk, a man of reliable cynicism, confided to a customer that he sometimes awoke in the night convinced someone was standing at the foot of his bed. “Never anyone there,” he whispered, his hand shaking as he bagged the customer’s groceries. “But I feel…observed.” When asked if he suspected Jefferson, the clerk paled and muttered, “Don’t say his name like that. Not here.”

The climax of this uneasy season arrived in August, with the annual Scandinavian Festival. Traditionally a cheerful bacchanalia of lefse, folk costumes, and mediocre fiddling, it had always been Junction City’s attempt to outshine its modest size. But this year, something was different.

The booths were arranged in a perfect grid, their canopies spotless and aligned like soldiers. The dancers moved in eerie synchronization, their smiles fixed, their steps so precise they resembled clockwork dolls. Even the food seemed altered: the meatballs rounder, the pastries flakier, the coffee brewed to an exacting standard that rendered it almost too perfect to drink.

At the center of it all, leading the parade, marched Tweed Jefferson.

He wore not a costume but a plain black suit, his posture immaculate, his expression unreadable. Yet all eyes were on him, willingly or not. His mere presence seemed to command it. When he lifted a gloved hand, the dancers froze mid-step, the crowd’s applause halted in their throats, and the only sound was the faint, keening hum of the obelisk from across town, vibrating in sympathy.

For a breathless moment, it seemed the entire town held still. Then Jefferson lowered his hand and life resumed. The parade marched on, but something essential had shifted.

One woman fainted, later claiming she had glimpsed, in that frozen instant, a shadow stretching behind Jefferson that was not a man’s shadow at all but something branching and endless, like the silhouette of a great machine. Nobody believed her, yet nobody doubted her, either.

By September, murmurs of dissent began. Quiet at first – half-formed jokes at the café, cautious glances at the obelisk – but dissent all the same. “What’s he after?” muttered the barber, clipping hair with trembling hands. “Nobody improves a town this much for free.”

A group of citizens proposed a meeting, an informal vote to “reassert community priorities.” The flyer read simply: We Decide For Ourselves.

The meeting was held in the high school gym. Hundreds attended, their faces tight with anticipation. The air was thick with both hope and dread. For the first time in months, people felt almost like their old selves – messy, argumentative, free.

But then Jefferson appeared.

He did not stride in; he simply was there, as though he had always occupied the far corner of the gym. His gaze swept the bleachers and the murmurs fell silent. The microphone crackled, went dead, and the gym’s fluorescent lights dimmed until the room glowed in a queasy half-light.

Nobody recalls what was said. Some insist Jefferson never opened his mouth. Others swear he spoke at length, though no words remain in memory – only the sensation of being addressed, intimately, as though each person were the sole audience.

When the lights brightened again, the meeting was over. No vote had been taken. People filed out calmly, their expressions placid. Later, when asked about the purpose of the gathering, most could not recall. “Just a community update,” they’d murmur vaguely. “Nothing important.”

The flyer disappeared from bulletin boards overnight.

It was the children who changed most visibly.

They began speaking of Jefferson with casual reverence, as though he were an old family friend. They played new games in which one child, playing “the Observer,” stood silently while the others marched in patterns. At recess, their songs grew stranger:

Step in line, keep the time,

Watchful eyes are yours and mine.

Teachers laughed nervously and told themselves it was harmless, but in the staff room they whispered about the dreams they’d begun to share – dreams of vast plazas, of towers stretching into a blank sky, of Jefferson standing at the center with his back turned.

One evening, a mother overheard her daughter whispering prayers not to God but to “the man in the suit.” When asked who she meant, the girl smiled beatifically and said, “He keeps the town safe.”

The final, most unsettling episode came in November, during a partial solar eclipse.

Residents gathered in the park with protective glasses and picnic blankets, prepared for a rare spectacle. As the moon began to slide across the sun, a hush fell over the crowd. Shadows lengthened, warped, grew unnaturally sharp.

Then, as the sky dimmed, the obelisk began to sing. Not faintly this time, but with a resonant, bone-deep tone that vibrated through the earth itself. Birds wheeled wildly overhead. Dogs whimpered. The crowd clutched their ears, yet none fled.

And Jefferson stood at the base of the obelisk, his face uplifted, bathed in the eerie half-light of the eclipse.

Some swore his figure elongated, stretching impossibly tall against the dimmed horizon. Others claimed they saw dozens of reflections of him in the obelisk’s polished surface, each one turning its head a fraction out of sync with the real man.

When the sun returned, the sound ceased, the shadows normalized, and Jefferson was gone.

The townspeople dispersed silently, shaken but calm, as if soothed by some unspoken promise. That night, not one person reported trouble sleeping.

In the weeks that followed, life continued – tidy, prosperous, strangely muted. The streets gleamed, the markets thrived, the children marched in step. Outsiders visiting from Eugene remarked how pleasant Junction City had become. “Efficient,” they said admiringly. “Disciplined. There’s a serenity here.”

The residents nodded politely but said little. They knew better than to describe what that serenity had cost.

No one spoke openly of Jefferson. His name receded into a kind of collective silence, as if acknowledging him aloud might summon him. Yet everyone felt his presence. The obelisk still hummed on windy nights. The council still passed budgets no one remembered drafting. And people still, now and then, awoke at night convinced someone was standing at the foot of the bed.

They did not check.

Years later, no one could quite say when they last saw Tweed Jefferson. Some insisted he still strolled the farmers’ market, adjusting the angle of a bread loaf with the faintest smirk. Others swore he had left long ago, his work complete.

But the town remained as he had shaped it – orderly, obedient, prosperous, eerie. Outsiders admired it, insiders endured it, and somewhere in the silence between them, Jefferson’s shadow lingered.

Children grew into adults who did not remember a time before harmony. Old men died still wondering what, precisely, had been taken from them. And the obelisk sang, faint and sweet, whenever the wind shifted.

As for Jefferson himself, perhaps he had never been a man at all, only the embodiment of some civic hunger for order, some latent yearning for control. Or perhaps he remained, quietly observing, waiting for the next town in need of a darker kind of salvation.

No one could say for certain.

But on some nights, when the wind carried that low, humming note, the people of Junction City found themselves walking in step without meaning to, their shadows lengthening unnaturally beneath the streetlamps. And though none spoke of it, each felt the same thought flicker, unbidden, across the mind:

He is still here.